Why AI can't learn on the job

And how that might change

Welcome to Tech Futures Project, exploring the political economy of AI and tech.

AI Amnesia

LLMs can pass the bar exam but can’t remember what you told them five minutes ago. This paradox points to a major bottleneck preventing AI from transforming the economy: continual learning. LLMs still don’t have a way of updating their long-term memory on the fly.1 Some have argued that this is a major reason why AI still isn’t replacing human jobs (or task) at scale. Humans learn on the job and get better over time in ways that are hard to fully fit into a context window but even if an LLM is used every day for a year its weights are unchanged.2 ChatGPT, Claude etc. have workarounds (‘Saved Memories’) where they summarise and stuff facts into the context window to help adapt to your needs over time, but this is a rudimentary approach and falls down in the face of complex learning. To use an inadequate analogy with the human brain, an long-term memory is frozen solid after it is trained and the only way to let it remember is through stuffing as much context as possible into its working memory (context window). LLM memory is therefore limited to ‘a short window of present and long past … which results in continuously experiencing the immediate present as if it were always new.’3 In a sense, LLMs operate outside of chronological time. They are simultaneously in an eternal present (their context window) and a history-less past (their weights).

Hope Architecture

Researchers at Google, inspired by the human brain, believe they have a solution to this problem.4 Their ‘Nested learning’ approach adds more intermediate layers of memory which update at different speeds. Each of these intermediate layers is treated as a separate optimisation problem to create a hierarchy of nested learning processes. They believe this could help models continually learn on-the-fly.

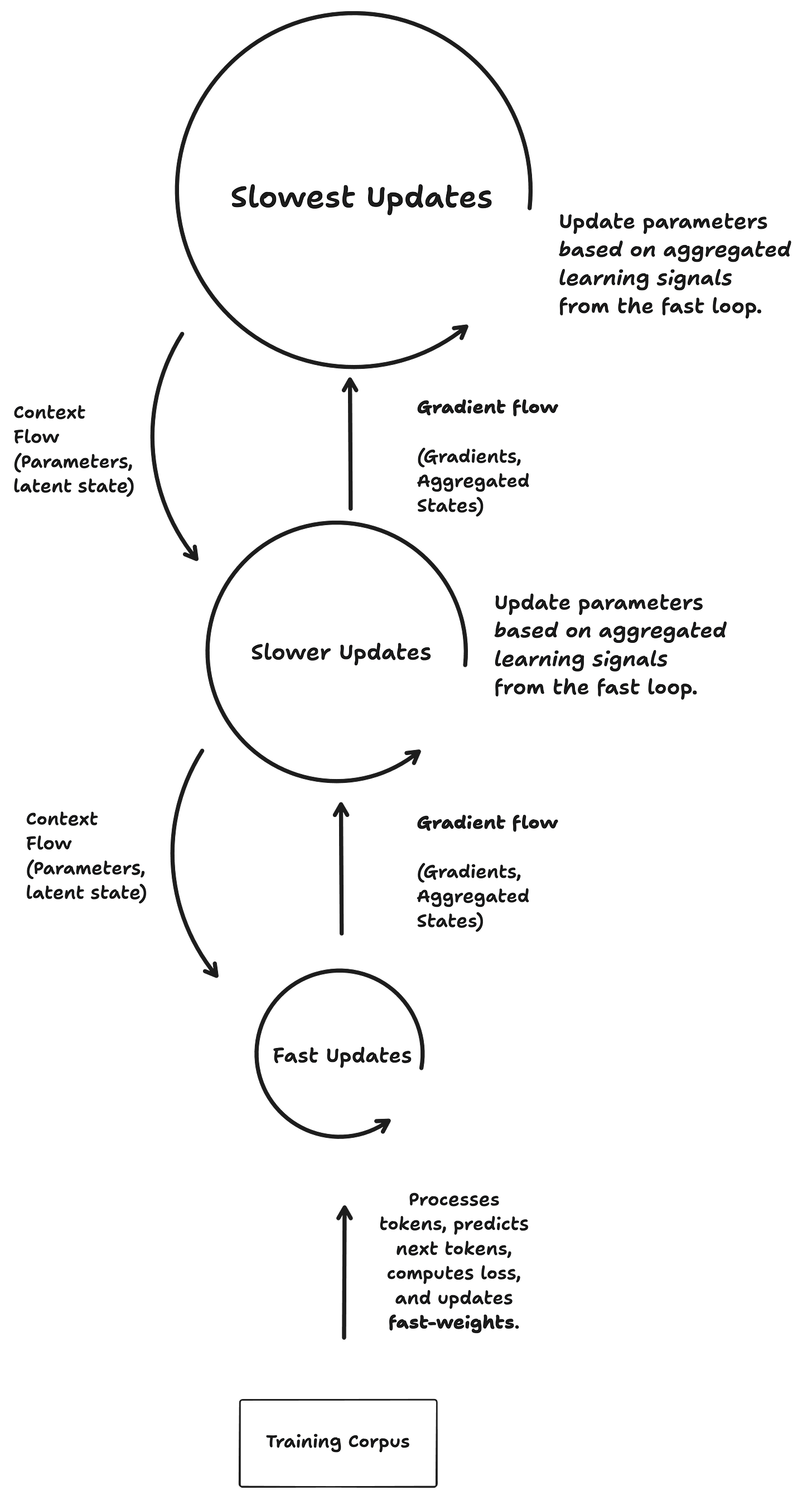

Critically, in their HOPE architecture (High-order Optimization and Parameter Evolution) they enable the model to learn how to learn. The fast loop trains in a way that is similar to current architectures (Predicts the next token, computes the loss and updates its weights). It then sends information (in the form of gradients) up to the slower loop. In return the slower loop sends the fast loop back context (hyper-parameters and latent states). This same process happens between the slower loop and the slowest loop. Gradient flows go up and context flows come down.5

This feedback mechanism between faster and slower learning loops enables a meta-learning system. The slow loops learn how the fast loops learn. They provide stability and learning tips (in the form of their longer-term guidance and learning tips, in the form of hyperparameters). This allows the system as a whole to continually improve as learners and not just as performers and avoid the catastrophic forgetting issue which has cursed ML models.

Remembering AI

The impact of this architecture (if it works on a large scale) could be immense. If models could continuously learn (and perhaps actively acquire information) I think one of the main impacts might be on our conception of time. Human learning speed slows things down substantially. If you want to start a business you have to learn about your users, your optimal processes etc. If you want to start a political campaign you have to learn how to work together, where the key leverage points are to make change etc. This architecture could conceivably change this logic. If LLMs could learn continuously at speed, its hard to see how this wouldn’t destabalise our conception of time (what would short-term, medium-term and long-term then mean), especially if this was paired with more agentic AI making decisions in the economy.

It’s far from certain this will work though. In the paper they prove the efficacy of the model on a small scale (~1.3b parameter model) but it would need to be proved on a much larger scale (Gemini 3 was 1 trillon parameters). The more serious problem is how the model actually works out what to keep in long-term memory. The authors take a specific perspective on memory. Specifically they take a connectionist view, inherited from behaviourism. In the context of this paper everything is association.6 Memory, therefore, is an associative engine trying to compress data. This architecture optimises by minimising ‘local surprise signal’. The human learning system is complex and we have spent thousands of years refining our information environment so that humans can assimilate and accomodate (in Piagetian terms) new information. Leaving the question of what to retain in long-term memory to this meta-learning system adds another dimension upon which the system could hallucinate.

Older ML models (such as RNN and LSTM - Long Short-Term Memory) were designed specifically to be able to update (in the LSTM case via selective ‘gates’). There have been recent attempts to deal with this problem for LLMs, such as S4, Mamba, Striped Hyena etc.

With current AI the only way to enable models to remember context is through stuffing it into the context window or retrieving it from an external store (like a RAG database).

This is related to a long-standing issue in model training: ‘catastrophic forgetting’.

Another interesting approach to enabling AI to update weights on-the-fly is test-time adaptation. It’s not exactly a memory layer but allows models to update their weights continuously.

These should actually be concentric circles, but this diagram is just for clarity of understanding. So the flows aren’t actually up or down necessarily.

Constructivists (e.g. Piaget) would argue that memory involves reconstructing knowledge to build schemas.